EU-UK environmental cooperation: Is the backstop the Goldilocks option?

Environmental protection is often thought of as a national responsibility, while trade agreements are seen as outward-looking. However, the distinction is blurred in discussions about the UK and EU’s future relationship. This is because a significant part of the process of developing, monitoring and enforcing UK environmental regulation currently happens at the EU level.

One of the sticking points in cross-party talks is how the UK and EU will continue to cooperate on environmental protection. Will the EU continue to play a role in benchmarking, or even enforcing, UK environmental rules?

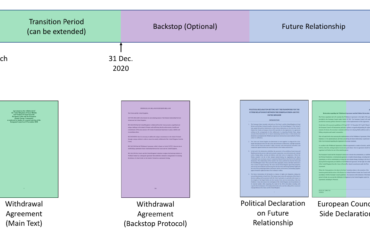

The Irish backstop already includes some environmental provisions, which are significant as, according to the Future Relationship Declaration, the UK and the EU will build on them in any future trade agreement. These provisions include commitments to non-regression of environmental standards (Withdrawal Agreement Annex 4, Part 2).

Yet recent articles, based on the German Repasi report, argue that this ‘environmental backstop’ would ‘undermine EU standards’. Parliamentary scrutiny has also led to the conclusion that UK domestic environmental protection plans will result in ‘significant regression’ of EU standards.

So which will it be: environmental non-regression or significant regression? Here I examine whether the environmental provisions in the backstop are a ‘Goldilocks option’, and why the UK has, arguably, already breached its requirements.

An innovative model

The backstop does not require the broad alignment with EU environmental legislation of the EU Association Agreements or the European Economic Area Agreement (which, in the Goldilocks analogy, may be ‘too hot’). Nor does it replicate the arm’s length – and unenforced – environmental requirements in EU trade agreements with countries like Korea and Canada (‘too cold’).

Instead, it allows the UK to diverge its regulation, as long as both Parties commit to maintaining current ‘common standards’ of environmental protection in a virtually comprehensive list of areas. The requirement is unenforceable: there can be no sanctions for non-compliance. However, the UK – and not the EU – is required to monitor and enforce its environmental regulation in order to achieve this. The EU can utilise the enforcement mechanism of arbitration if it feels there are shortcomings in UK domestic environmental enforcement. (For a more detailed summary, see here.)

Are the backstop’s environmental commitments just right?

In terms of regulatory provisions, the backstop presents a mirror image of most trade agreements, in that, with the exception of special requirements for Northern Ireland (Annex 5), it contains a greater emphasis, and more requirements, on broader environmental regulation and not just regulations specifically pertaining to traded products (e.g. in trade parlance, Sanitary and Phytosanitary Regulation and Technical Barriers to Trade). This indicates that the EU views effective UK environmental protection as a core priority of its trade relationship with the UK.

Given this already remarkable environmental emphasis, we couldn’t really expect a greater role from the EU in enforcing UK environmental regulation without the UK moving toward greater overall regulatory integration with the EU – an Association Agreement or Single Market model.

Yet, for reasons I examine further here, although a ‘Goldilocks approach’ seems sensible on paper, in practice it disappoints those who advocate for a greater role for the EU (as the previously quoted Guardian article demonstrates) as well as those who want to ‘take back control’ of UK regulation, as it gives the EU a role in monitoring UK environmental enforcement.

Arguably, the UK has already fallen short

The backstop requires the body that enforces UK environmental law to be able to initiate an inquiry when it believes the UK Government has breached an environmental law, and bring legal action with a view toward an ‘adequate remedy’ (Annex 4, Article 3:2). It also commits the UK to providing effective remedies for environmental lapses.

The UK has proposed an Office for Environmental Protection (OEP) in its draft Environment Bill. However, the OEP as currently envisaged will be unable to initiate investigations or make binding recommendations, even if it finds that a UK public body has seriously failed to enforce environmental law (Sections 18-29). This contrasts with the EU Commission, which is required to ensure enforcement of EU rules. This has often resulted in the UK facing the ECJ for environmental non-compliance, a process that can ultimately result in fines. In contrast, the draft Environment Bill allows for judicial review, a more limited form of scrutiny.

The backstop would likely not be enforced often

The EU’s interest in UK environmental protection is based upon its concerns that the UK will gain a competitive advantage through de-regulation. The Commission has estimated, for example, that if the UK lowers EU industrial emissions requirements, it could provide UK industry with a €4.7 billion per year gain.

Given this motivation, it seems most likely that the EU would pursue enforcement only if its competitive interests were clearly at stake. The deregulation concerns about industrial emissions and pollution that motivated these provisions are also most likely to prompt a contentious dispute. In other words, unlike the EU system of enforcement, the backstop is unlikely to function as a broad environmental protection mechanism.

This will likely be an area for future disagreement

The backstop’s environmental provisions leave many questions unanswered. Primary among them is how, and to what extent, the UK and EU will continue to cooperate and coordinate, as environmental law is a swiftly-evolving area. Corbyn has proposed ongoing ‘dynamic alignment’ with EU standards. However, it is unclear how this would operate in practice, or be understood and reciprocated by the EU absent fuller regulatory integration (recall that the EU rejected May’s earlier proposals for sectoral alignment).

Meanwhile, the UK government’s current position, laid out in its Chequers proposal of last summer, is to align with the EU on much product-related regulation whilst diverging on environmental regulation. EU Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier has stated that fears of UK environmental and social deregulation increasing its competitiveness could lead to ‘major difficulties’ ratifying a future agreement; if countries perceive this ‘everything is over’.

Clearly there is a mismatch between the UK’s proposal on environmental regulation and what the EU seeks. As a result, the extent of environmental cooperation will likely continue to be a contentious issue at the centre of both the intra-UK debate and negotiations with the EU.

About the author

Dr Emily Lydgate is a lecturer in Law at the University of Sussex and a fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Photograph courtesy of Erzsébet Apostol.