Significant challenges ahead for the Great Repeal Bill

How will the Great Repeal Bill ‘transfer’ EU law into UK law? In this blog post, Dr Apolline Roger (Sheffield Law School) argues we need to distinguish between substantive & institutional norms. This helps sketch out 5 types of environmental legislation and the challenges each faces.The UK government’s ambition is to transfer all existing EU laws into UK law when leaving the EU. But what does this entail in practice?

EU law, like all laws, sets ‘norms’ – rules of conduct. Some of these norms are ‘substantive’, they determine ‘what’ has to be done: for example, a dangerous substance is banned, companies should inform public authorities on the nature and quantity of the chemicals they use, or endangered species cannot be killed, etc. The others are institutional, they determine ‘who’ is in charge of implementing the substantive norms and how. For example, the European Chemical Agency is in charge of making sure that companies provide the correct information, the Member States share the load of identifying which substances are dangerous, etc.

The difficulty of the task facing the great repeal bill will depend on the nature of the EU norm at stake: is it substantive or institutional?

Substantive norms already apply in the UK, either directly, or through the national text that transposed them into UK law. No ‘transfer’ is needed: substantive norms just need to be confirmed as belonging to UK law which, legally speaking, can easily be done. However, substantive norms are only the tip of the iceberg. The main role of EU law is to distribute tasks between the EU institutions and the Member States in order to achieve the common objectives it sets. In this context, a great deal of work is needed to ensure the smooth transition the great repeal bill aims at.

For institutional norms, much more than a ‘transfer’ is needed: a whole new institutional system has to be invented.

The first step of this process is the identification of which tasks are currently ensured by EU institutions or which rely on cooperation among the Member States as set by EU law. Second, it is necessary to determine how these tasks can be renationalized. This process, which is supposed to guarantee a smooth transition through the great repeal bill while simultaneously maintaining the same level of protection, will be no walk in the park for environmental law, for three reasons.

First, the process will require an enormous amount of work and expertise as there are more than 300 pieces of environmental legislation. EU environmental law covers a wide range of issues; including: climate, nature conservation, industrial emissions, agriculture, fishery, chemicals, water, access to information, energy efficiency and energy mix, etc. This productivity is due to the very nature of the issue at stake. Environmental pollution does not stop at national borders and its regulation potentially impacts trade and competitiveness. Finally, finding a solution to complex environmental problems can be hard, and international cooperation can ease the load. For all these reasons, the Member States have decided to act together at EU level to solve environmental issues.

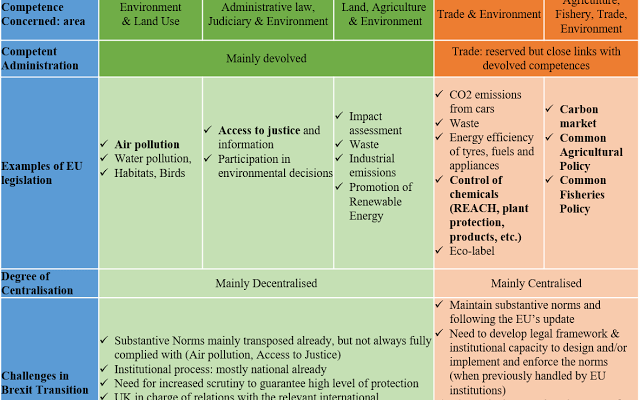

Second, preparing the great repeal bill will require a case-by-case analysis of each piece of legislation to determine who, for each issue, is doing what and how. Not all environmental legislation distributes tasks between the EU institutions and the Member States in the same way. Each created institutional mechanisms tailored to the issue at stake. In practice, it means that a case-by-case analysis is necessary to identify the governance system created by each piece of legislation. The task is arduous, but classifying EU environmental norms by the type of objective they pursue can offer a useful guide to anticipate how the repartition of tasks between the EU and the Member States is organized. Table 1 (below) shows how such typology can be used to organise the reflection by anticipating which issue is more ‘centralised’, i.e. situations in which the piece of legislation gave EU institutions the task to directly update and implement its provision. These situations consist of ‘hot spots’ – they are the issues which will require the most work to prepare the great repeal bill. A classification by objective can be useful for another reason. It highlights the repartition of competence between London and the devolved administrations within the EU (also organized by issue) and therefore helps to identify to whom the renationalized tasks should go.

Third, re-nationalising the tasks currently managed by EU institutions will not be straightforward. Maria Lee and Liz Fisher have discussed in an earlier blog that leaving the EU means the loss of an external accountability system. This loss could lead to a lowered level of environmental protection but (or precisely because) it is an opportunity for the UK government to be fully independent again. But being fully independent also comes with its own challenges.

Some EU environmental legislation created entirely new institutions, to replace or support States in the adoption and implementation process (mostly regulation type 4 and 5 in Table 1). This is, for example, the case of the European Chemical Agency which manages the implementation of the main chemical regulation, called ‘REACH’. In addition, many EU environmental laws share the workload between the Member States, for example, to identify new dangerous substances or organise cooperation to ease the implementation efforts. The UK is, today, part of these networks. It contributes and benefits from the cooperation. It also benefits from not having to conduct the tasks which are currently completed by the European institutions, and which can be resource heavy.

If the government, as announced, wants to maintain the current level of environmental protection post-Brexit, it will be faced with two options:

- Maintain cooperation with EU institutions if accepted by the negotiating partners; or

- Create or adapt institutions to absorb the new renationalized tasks. The complexity of this process should not be underestimated.

The institutions will need to be provided with adequate resources, expertise and the capacity to handle the new tasks. The system will have to be respectful of the devolved administrations competences, and make sure that environmental policy at large is still coherent, relevant and efficient.

Table 1: Typologies of environmental norms* and their relation to internal competences (Particularly challenging areas are in bold.)

*EU legislation can be mostly divided into five main typologies; however, some legislation does not fit neatly into a typology.

Dr Apolline J.C. Roger is a Lecturer in Environmental Law at the University of Sheffield Law School. She recently contributed to a SULNE report on The implications of Brexit for environmental law in Scotland.