Brexit & Environment

Independent research and resources

Challenges

Governance

Devolution

Environment is a devolved issue. The administrations of Westminster, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all have diverging preferences on how environmental policy should be made now the UK has left the EU.

Several important issues are arising. How will UK environmental policy be coordinated post-Brexit? How will minimum standards be decided and by whom? Do devolved administrations have enough capacity and resources to develop, implement and enforce environmental policy? What are the implications for different sectors (including agriculture and fisheries, which are also devolved)?

Legal matters

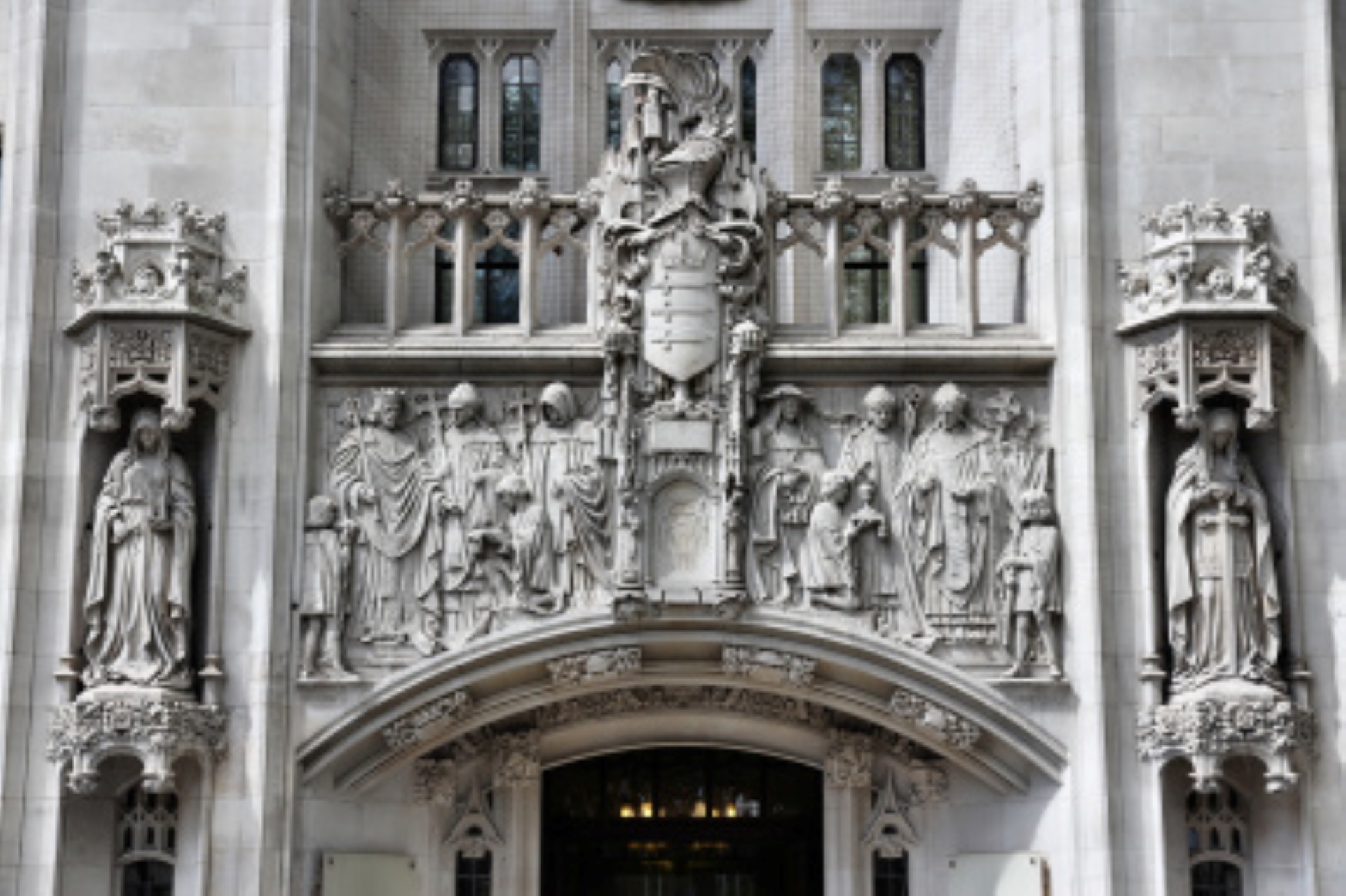

Leaving the EU has raised many legal questions.

The Government ‘cut and pasted’ EU environmental rules into UK law via the EU Withdrawal Act to prevent regulatory holes emerging when the UK left. However, what happens to ‘EU retained’ law now that the UK has left the EU?

Another concern is whether all levels of government (including the devolved administrations) have sufficient capacity to develop, implement and enforce environmental policy – tasks that for the last 47 years were largely carried out at EU level.

Lastly, without recourse to the Court of Justice of the EU, how will NGOs use the new watchdog (the Office Environmental Protection) to ensure the Government implements its environmental policy promises?

Trade

The UK has signed a new Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU, which has significant implications for the way in which policy is made in Brussels, London and the devolved administrations.

During the negotiation of the TCA the EU was determined to ensure that the UK maintains EU standards and does not return to being ‘the dirty man of Europe’.

The prospect of brand new trade deals with other countries such as the US and Australia, however, raised concerns about the lowering of UK environmental standards to achieve a competitive advantage.

New trade agreements will have implications for associated sectors, such as agriculture and food, which are dependent upon access to migrant workers, have ‘just in time’ supply chains and whose profitability relied heavily on EU exports and imports.

Policy

Agriculture

Leaving the EU meant leaving the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Brexit provides an opportunity to rethink current policy and possibly make it more efficient and sustainable.

Leaving the CAP also poses challenges, however. Agriculture is a devolved issue, yet it is the UK administration that negotiated Brexit and any future trade deals, which could have a significant impact on devolved agricultural and environmental policies. Meanwhile, meeting EU process and product standards will remain a requirement for UK farmers if they wish to access the EU market.

Finally, new trade deals could open up UK agricultural markets to new competition, drive some farms out of business and heap pressure on the Government to weaken environmental and animal welfare standards.

Air Pollution

Air pollution across Europe is firmly on the policy agenda, with many European countries failing to meet EU standards for air pollution.

Air pollution is a transboundary problem – pollution in one country can have negative impacts in another, as was the case with acid rain in the 1970s. This raises questions of future collaboration between the UK and the EU on reducing air pollution.

Air pollution is also at the heart of a long running legal battle between the environmental group Client Earth and the UK Government. This battle hinges on the binding nature of current EU rules, raising questions about the ability of civil society to hold the government to account after Brexit.

Climate Change

Brexit is impacting both UK and EU climate change policy. The UK has traditionally been a supporter of more ambitious EU climate policies and Brexit could conceivably weaken the EU’s progress.

In the UK, however, there are concerns that Brexit negotiations will divert attention from climate change and that the lack of external pressure from the EU will allow the government to weaken climate regulations.

Fisheries

Brexit involved leaving the Common Fisheries Policy and was an opportunity to rethink and improve fisheries policy in the UK to make it more sustainable.

Fish stocks move across borders, however, so the UK will still need to cooperate with the EU in some way to ensure the sustainable management of our marine resources. There is also a risk that leaving the EU will weaken existing environmental protections and enforcement of fisheries and conservation regulations due to a lack of civil service capacity.

Future trade agreements with other countries will affect both the marine environment and profits, employment and rural development in fishing communities.

Waste

EU waste legislation played a key role in shifting UK policy from landfilling most waste to ensuring more waste reduction, recovery and recycling.

International trade in waste (to ensure that it can be disposed of in the most efficient and environmentally friendly way) will need to be considered in creating future waste policy. The ways in which waste policy is shaped will affect both the waste sector that earns revenues from handling waste, and businesses that are required to take responsibility for waste issues created by their products.

Key questions for the UK as it adapts to life outside the EU include: will it maintain EU waste standards? Will the UK’s waste policies weaken or become stronger? And will Brexit incentivise new and more ambitious waste policies.

2020 ©Brexit & Environment