Late mover advantage? Designing a post-Brexit environmental watchdog for Wales

Brexit opened environmental governance gaps in the UK. During the UK’s membership of the EU, many practical environmental governance functions, from setting long-term targets to monitoring practical conditions and enforcing compliance with environmental law was done (in part) by EU institutions. Brexit triggered a review of those arrangements: were some functions not needed anymore? If they were needed, could we ‘make do’ with existing bodies, or were new bodies needed?

All of these questions were made more difficult as ‘we’ in those questions is tricky to narrow down. The UK yes, but not just the UK government – environment is devolved which means different parts of the UK, Scotland, Wales, England and Northern Ireland, may address these questions differently and at different times. And ‘make do’ is also questionable – according to whom? Whether we need to reform, improve, fund differently environmental governance can become a political quagmire, as evidenced by the never-ending debate on establishing an independent environmental protection agency in NI.

Watchdog needed

Out of these gaps, the gaps in enforcement, and the role the European Commission and Court of Justice of the EU played in holding governments to account, are the ones that gathered the most attention. New watchdogs were set up for England and Northern Ireland (the Office for Environmental Protection) and in Scotland (Environmental Standards Scotland). But what of Wales?

Since 2021 Wales has ‘made do’ with the Interim Environmental Protection Assessor for Wales. IEPAW is comparatively under resourced, with far less power than the OEP and ESS. It is also less independent than either of those two, even though independence questions remain for both the OEP and ESS. The Welsh Government is now running a consultation included in a White Paper on a proposed environmental governance body that could take the form of an Environmental Commission. It is a fascinating document with both a good primer on how Wales has been regulating the environment quite differently since the devolution settlement of 1998 and frequent mentions of what the EU did – in stark contrast to the Westminster Government which favoured a tabula rasa approach to environmental governance (as seen for example in the 25 Year Environment Plan) with barely any mentions of the EU or past EU membership. This post is the first of three considering the consultation. The next two will focus on principles.

How do Welsh proposals compare?

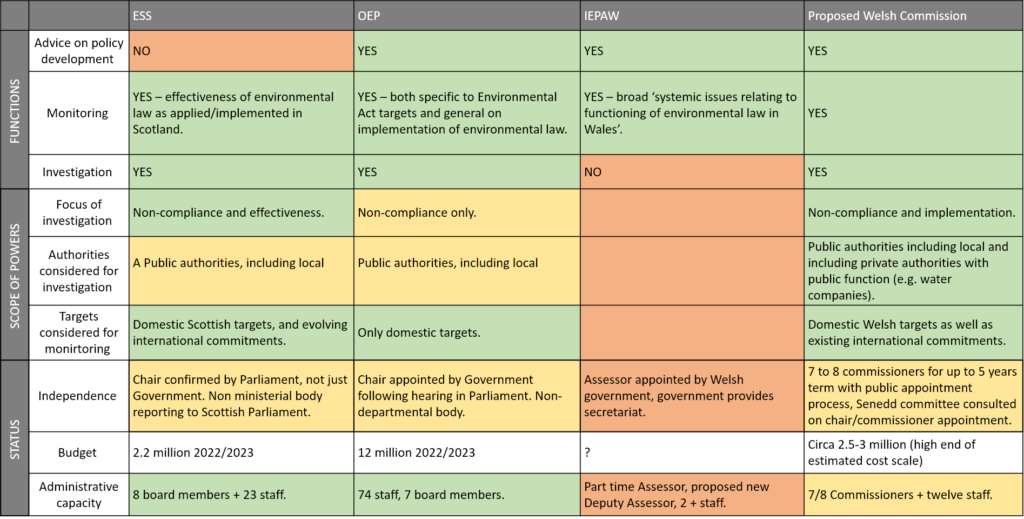

Wales is moving last, so what lessons (if any) is the Welsh government drawing from the work of its own IEPAW, and of the two more fully fledged bodies in the rest of the UK?

OEP and ESS went in two different directions. OEP is better resourced, but less independent. It is also trying to do more – with advice on policy developments in addition to monitoring and compliance investigations which the ESS focuses on. IEPAW focused on those first two tasks – monitoring and advice. The proposed Welsh Commission, as seen in the table above, is spanning all three tasks and hoping for the best of both worlds. As its Scottish counterpart it will consider delivery against both devolved and international targets (whereas international targets are outwith scope of OEP). As its Scottish counterpart, it will consider not just non-compliance in its investigations but broader issues of implementation and effectiveness, effectively doing an evaluation of the quality of the law and its implementation not only whether it is being complied with. It goes further than ESS to propose issuing compliance notice for failures to exercise both non-regulatory functions as well as regulatory functions. As its English and NI counterpart, and IEPAW, it will offer advice on policy development. It will also do things slightly differently: whereas both OEP and ESS focus on public bodies, the proposed body could also investigate private bodies “exercising functions of a public nature” such as water companies.

In summary, the proposed Commission appears to be trying to aim for the best of both worlds. But this comes with three issues. First, the consultation is silent on the transition between IEPAW and the new Commission. This raises concerns of both growing pains for the new watchdog and uncertainty, if not outright governance gap, in the move from one body to the other. Second, the OEP’s own experience of having one body providing, advice, monitoring and investigating compliance is not wholly positive, with the OEP experiencing multiple ‘rubbing points’ with DEFRA. It is very difficult for a body to be both close enough to be listened to and distant enough to be able to hold the government to account. Third, ESS is more focused (and the Scottish Parliament plays a more central role in governance compared to the House of Commons) but it is also less resourced than OEP. The proposed Welsh Commission is thus trying to do as well as the ESS and OEP together – with a much smaller workforce (twice less staff than Scotland, six times less than the OEP (which covers two jurisdictions). As it stands, the consultation is giving the new Commission an impossible task.

11 April: This post was amended to update budget for proposed Welsh Commission in Table 1.