The Windsor Framework and the Environment

This blog post discusses the implications of the new Windsor Framework for the environment. Much at this stage remains uncertain – who will support the Framework, how the political agreement will be interpreted in legal texts (still forthcoming), how they will eventually be implemented in practice. But the Framework’s environmental side is worth investigating, for what it tells us about the place of environmental action in UK-EU relations, but also because each revision of the specific Ireland/NI arrangements have seen a drop in environmental ambition.

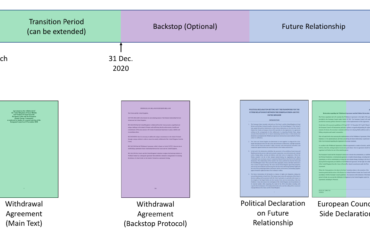

The first iteration – back in 2018 – of the Protocol on IRE/NI (‘the Backstop’) in PM May’s version of the Withdrawal Agreement was surprisingly ambitious on the environment. It even included a whole article on “non-regression in the level of environmental protection” (see draft UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement, Protocol on IRE/NI Annex IV, Part Two, Article 2), which incorporated a broad remit of environmental issues (including for example access to environmental justice, air pollution, marine and freshwater protection, chemicals and climate change) as well as the four EU environmental principles. The following Article 3 of the ’Backstop Protocol’ addressed “monitoring and enforcement related to environmental protection” – its requirement for a UK “independent and adequately resourced body or bodies” to enforce relevant EU laws fueled domestic demands for new environmental regulators which became the OEP in England and Northern Ireland), the ESS in Scotland and the Interim Assessor in Wales.

Each revision of the specific Ireland/NI Brexit arrangements since 2018 have seen a drop in environmental ambition.

Boris Johnson’s revised Protocol on IRE/NI – agreed in 2019, which then entered into force in early 2021 – was already markedly less ambitious. Gone were any requirements on environmental governance and the scope of environmental issues considered was also much narrower. Only those EU environmental rules most directly connected to trade in goods were included (e.g., shipment of waste and chemicals remained but water and biodiversity were out).

The newly revised Windsor Framework (f.k.a. the Protocol) marks a further step back. In this first blog post we explain how it casts discussion about EU rules as a matter of cutting red tape, but risks undercutting NI producers on their own market and makes NI much more susceptible to deregulatory winds from Westminster. On governance issues (in our second post coming tomorrow) we argue that the Framework marks a move away from strong UK-EU support for North/South cooperation on the island (which raises specific environmental concerns) but that it marks a step further for inclusion – of both NI elected representatives and NI civil society – with uncertain impact on dynamic alignment and environmental ambition.

The Windsor Framework reinforces discourse of EU law as red tape/regulatory burden

The emphasis in how the deal is being sold by Rishi Sunak is on a marked reduction of EU law applying in Northern Ireland – making Northern Ireland “the world’s most exciting economic zone”. At this stage there is still a lot of uncertainty and lack of clarity on what exact parts of the EU acquis, currently residing in the 2019 NIP annexes, will apply, to what (agri-food, parcels, retail goods….) and to whom (GB to NI traders, NI producers, NI to EU traders). But the rational for those rules is purely economic: “The rules that do apply are there solely, and only as strictly necessary, in order to maintain the unique ability for Northern Ireland firms to sell their goods into the EU market” (UK Command Paper).

Overall, what appears to be developing with the Windsor Framework is a type of ‘Schrödinger’s EU Law’, de jure in force in Northern Ireland, but de facto put aside, if and only if traders meet the requirements for the Green Lane. The Windsor Framework shifts the focus from the Protocol away from what is happening in Northern Ireland to trade between GB and NI. This is likely to be greatly welcomed, particularly by traders who rely heavily on GB-NI movements – but such facilitation will also create new challenges and complexities for NI producers and consumers.

For agri-food goods coming into NI from GB and entering under the so-called ‘Green Lane’ procedure, UK(GB) food safety standards will apply. For industrial and retail goods coming into NI from GB, via the Green Lane, compliance with an even smaller subset of EU law will be required. The extent to which these rollbacks in the application of EU law also extend to NI producers remains somewhat unclear. Based on prima facie reading of the draft Joint Committee decision, it seems that the rollbacks only apply to goods entering NI and will not apply to NI producers. There is a risk therefore that NI producers are put at a competitive disadvantage in their own markets with goods entering from GB and sold on the NI market need not comply with the (anticipated higher) regulatory standards of EU law which will still apply in Northern Ireland under the Windsor Framework. Alternatively, if as the details of the (still draft) Windsor Framework continue to be worked out, producers located in NI can operate under Green Lane requirements when placed goods on the NI market, this will increase the risk for the EU Single Market inherent in this novel framework.

What would this mean in practice for the few environmental rules in the Protocol? If we compare Annex II (2019 Protocol, still applicable, we think, to NI producers) to Category 2 (2023 Framework) which would apply to GB importing into NI under the Green Lane the difference is between over 250 EU rules and less than 50. Few environmental rules remain. For example, taking Waste; the NIP contains 4 directives and regulations, the WF only 2 (packaging waste or recycling have been removed). On chemicals, 7 out of 12 remain, most importantly REACH – this means GB producers selling into NI will still need to comply with EU REACH (in addition to UK REACH for intra-GB trade).

Implementation concerns arise if we consider the size of NI businesses – the smaller they are, the less likely they will be able to produce to two different sets of standards. Additionally, under this new system, any increase in divergence between UK and EU rules on either retail goods or agri-food products can be expected to result in an increase in administrative/cost burdens on NI businesses who will likely need to monitor the respective regulatory requirements on goods coming either: from GB for NI; coming from GB for EU; coming from NI for GB; coming from NI for EU.

The Windsor Framework exposes NI much more directly to Brexit regulatory changes

Many of the impacts of the Windsor Framework will only occur in conjunction with domestic legislation in the UK. Thus, for example, concerns about deregulation in England and its impact on the UK Internal Market, in particular the fear that this would allow English producers to undercut producers in devolved administrations bound to higher standards, had for been limited in NI due to the Protocol. Requirements to follow EU standards for food safety but also product and sometimes process standards meant that such a race to the bottom would not end up on NI supermarket shelves. But that is not the case anymore. Instead, NI, like Wales and Scotland, will have to fully engage with the structures created by the Internal Market Act and the Common Frameworks to try to limit such undercutting on its own market.

In addition, the fewer the number of EU rules applying comprehensively in NI, the more Brexit in NI is looking like Brexit in GB – which means that NI will likely be open to much greater deregulatory risks through the Retained EU Law Revocation and Reform Bill currently being discussed in the Lords than it would have been under the previous Protocol. In this respect, it is worth noting the unique exposure of NI to potential negative deregulatory effects due to its proximity to, and interrelation with, the Irish economy.

The fewer the number of EU rules applying comprehensively in NI, the more Brexit in NI is looking like Brexit in GB

From the perspective of legal certainty, the end of the NIP Bill is welcome. Given the extensive reliance of the Bill on the use of discretionary powers by Ministers of the Crown with limited accompanying requirements for reporting or accounting for their decisions in making law for NI, the effective replacement of the NIP Bill with the Windsor Framework strengthens the cause of legal certainty in NI going forward. That said, operationalizing the new arrangements is unlikely to diminish the standing problem of legislative complexity that is inherent in post-Brexit NI, indeed the Windsor Framework system may prove to exacerbate the issue.