Westminster and waterways: Strategies to protect water quality in Northern Ireland after Brexit

This article draws on a literature review and interviews conducted for an MSc dissertation titled “Basins, Borders and Brexit: Water Management on the Irish Border.” The author also published a shorter piece in Rural Water News, an online magazine based in the Republic of Ireland.

Now that the EU and UK have agreed to a Brexit extension until 31 January 2020, there is a prolonged period of uncertainty for policymakers across the UK. Specifically, for water body quality protection in Northern Ireland (NI), different Brexit scenarios could lead to very different outcomes.

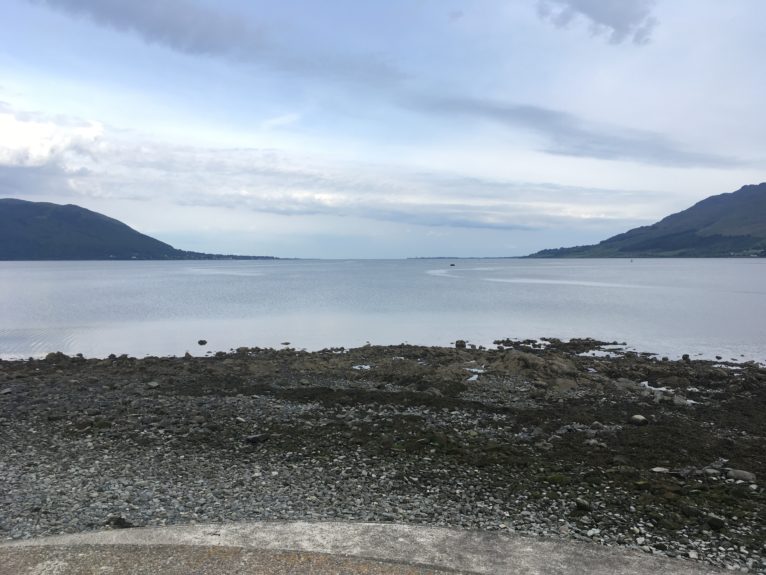

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) is the key piece of EU legislation for water quality protection. Under “soft” Brexit scenarios, the UK would continue to follow this legislation. On transboundary water bodies such as Lough Erne, Lough Foyle, and Carlingford Lough, EU regulations would continue to protect water quality where the water bodies cross into the Republic of Ireland (ROI).

However, while Boris Johnson’s proposed deal keeps Northern Ireland in line with some EU regulations (such as pesticides, waste, and invasive alien species), the deal does not require NI to follow the WFD. Johnson’s deal would therefore lead to divergence from EU regulations.

Like Johnson’s deal, no-deal would also threaten water body quality. A no-deal Brexit could lead to divergence in environmental protections between NI and ROI, which could threaten water body quality in both NI and ROI.

In this context, over the coming months the UK government should take five key actions to protect water quality in Northern Ireland in the face of Brexit uncertainty.

Current Government Situation

At the UK level, the government at Westminster is currently preparing for the election on 12 December 2019. The changes recommended in this article are not likely to be implemented until after the election.

At the NI level, there has been no government in Stormont since January 2017. The lack of a government gives bureaucrats disproportionate power in environmental policy decisions, makes high-level cooperation between NI and ROI more difficult, and hampers NI’s ability to prepare for Brexit. As one interviewee in NI suggested, “NI departments are hamstrung.” Stormont’s problems delay infrastructure repairs, leading to increased risks of water contamination from leaking wastewater. Because environmental regulations that could protect water quality are a devolved power, a restored government in Stormont would be necessary to update water quality legislation after Brexit.

Recommendation #1: Guarantee the UK will uphold Environmental Protections

Currently, water management is regulated by EU legislation such as the Water Framework Directive (WFD), Floods Directive, Habitats Directive, and Drinking Water Directive. NI benefits from streamlined cross-border cooperation when it shares regulations, standards, and goals with ROI. For example, the WFD classifies water bodies as “high, good, moderate, poor, and bad” status according to their level of pollution. In NI, approximately one third of water bodies are “good” or “high” status. Because NI and ROI share the same classification system, they can communicate about goals for pollution reduction.

The UK Government, while promising a Green Brexit, is also paving the way for weaker environmental protection. In the realm of water quality classification, the UK’s 25 Year Environment Plan proposes abandoning the current classification system and instead measuring the quality of water bodies as compared to their “natural state.” Instead of making this change, the UK should maintain the same classification system as the rest of the EU, especially in NI where water bodies frequently cross the border.

In addition, EU standards may be a moving target. Several interviewees discussed the ongoing reforms of the Drinking Water Directive, which would make source water protections more stringent in ROI and other EU countries by adding new quality parameters. After Brexit, the UK would lose its EU voting rights, greatly reducing its ability to push for its preferred legislative changes. However, its leaders should still aim to coordinate with the EU’s regulatory regime.

Recommendation #2: Ensure Adequate Funding for Environmental Programs

EU funding from programs such as Interreg and the Special European Union Programmes Body supports cross-border environmental protection programs on the island of Ireland that protect water bodies and encourage conservation. These include Source to Tap, Catchment CARE, SWELL, and GREEN-WIN. These programs have positive environmental impacts and bring together stakeholders across the border. However, after the current funding cycles are complete, they could lose funding from the EU and could experience a decreased prioritization of environmental protection in the UK. (Note that Johnson’s deal does indicate a goal of continued INTERREG funding.) For instance, the Source to Tap and Catchment CARE projects were both delayed due to Brexit uncertainty. To manage these risks and to continue the existence of these programs, the UK should guarantee their funding following any Brexit outcome.

Recommendation #3: Encourage Continued Cross-Border Cooperation

In the face of large-scale political discord, local cooperation between water managers in NI and ROI protects water bodies and brings communities together. While some of this cooperation is linked to EU funding, as discussed above, much of it is voluntary. Cooperation includes data sharing, lough cleanup efforts, and water level management. It also extends to drinking water supplies, an area which sees coordinated laboratory analysis, chemical supplies, and emergency drinking water delivery. Westminster should encourage this cooperation by providing funding and technical support to groups near the border.

Recommendation #4: Prevent Pollution

Brexit opens the door to increased water pollution. First, price differences after Brexit could cause increased smuggling of fuel, waste, and other items. Smugglers on waterways who are about to be caught sometimes dump the items that they are transporting, often to detrimental effect to water quality. Second, Brexit could disrupt cross-border movement of dairy products and animal waste, and there is a risk that these products could be dumped in rivers. The UK should use increased monitoring and education campaigns to reduce these potential impacts.

Recommendation #5: Decide Soon

The tremendous uncertainty caused by drawn-out political negotiations makes it difficult for water managers to plan appropriate responses to the risks discussed above, as was highlighted by several interviewees from NI, ROI, and international organizations. Once the UK and EU determine final Brexit arrangements, water managers will be able to prepare themselves for the future.

Conclusion

Risks to water body quality in Northern Ireland are a serious yet largely unpublicized effect of Brexit. Policy changes are not likely to occur until after the election on 12 December 2019. After the election, the UK government can support NI water managers by upholding environmental protections, providing funding and support for cooperation, and preventing pollution. The sooner Brexit outcomes are determined, the faster water managers can respond in these areas.

About the author

Andrew Tabas is a researcher at The Nature Conservancy-Oxford Water Partnership and holds an MSc in Water Science, Policy and Management from the University of Oxford.

He would like to thank Dr. Troy Sternberg for his supervision of the dissertation and Dr. Brendan Moore and Dr. Viviane Gravey for their comments on this article.