A tale of two plans: UK and EU post-Brexit policy

The 25 Year Environment Plan published last month offers an interesting opportunity for the UK Government to project itself beyond the daily grind of everyday politics. Much delayed, it nonetheless sets out a long-term strategy for the environment – primarily in England and perhaps eventually for the whole of the UK.

However, considering the plan was repeatedly pushed back after the referendum to deal with Brexit, it has very little to say about Brexit or indeed the EU. In fact, it remains very vague about where the plan builds upon EU membership, merely stating that ‘some of the targets derive from our membership of the EU while others go further than EU rules require.’ It also fails to explain how it will build on and perhaps go beyond the EU’s Seventh Environmental Action Programme and the system of governance in which it is embedded.

Below, beyond or still bound by EU policy targets?

This vagueness is highly problematic. First, the 25 Year plan is unclear whether targets are pre-existing and based on current EU commitments, which would be carried over in the EU Withdrawal Bill or conversely whether they are new and then how they will differ from the status quo. This hinders attempts to evaluate how ambitious the plan really is and whether it is really (and I quote) ‘drawing on the opportunities leaving the EU provides’ to do things differently.

For example, take the objective for marine biodiversity: ‘Reversing the loss of marine biodiversity and, where practicable, restoring it’. This aim is already present in the EU’s 2008 Marine Framework Directive. More worryingly, the EU’s Water Framework Directive aims for good status for all-natural water bodies by 2027 at the latest, yet the 25 Year plan makes a weaker commitment to improve ‘at least three quarters of our waters to be close to their natural state as soon as is practicable’.

While it is unclear how ‘natural state’ and ‘good status’ differ, the reduced amount of water bodies concerned, the vague date (as soon as practicable) and the vague objective (how close is close to?) suggest a reduced ambition for water quality. This apparent roll-back is in one of the rare objectives that has a numerical target. Yet many of the other objectives in the Plan are very loosely phrased – e.g. ‘Maintaining the continuous improvement in industrial emissions by building on existing good practice and the successful regulatory framework’.

Crucially, such phrasing will make it very difficult to evaluate whether the government meets its objectives to ‘to leave our environment in a better state than we found it’.

A tale of two plans

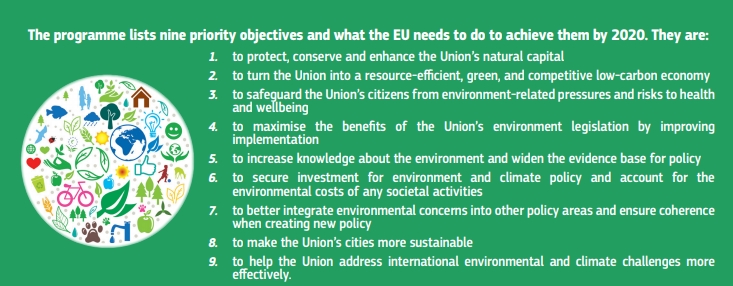

Second, while the 25 Year plan is a departure from normal UK government practice, the EU has adopted seven Environmental Action Programmes since the early 1970s, all setting out medium-term objectives. The UK has been a full party to all of them. The seventh environmental action programme runs to 2020. Comparing the two plans can shed light on how policy planning will change after Brexit.

Like the 25 Year Environment Plan, the seventh Environmental Action Programme has a list of key objectives. The two plans’ objectives are, however, expressed with different degrees of certainty. Hence both have objectives on resource efficiency, but while the 7EAP aims to ‘turn the Union into a resource-efficient, green and competitive low-carbon economy’ the 25YEP focuses on ‘Using resources from nature more sustainably and efficiently’. And while the 25YEP stresses the originality of adopting a Natural Capital Approach, the 7EAP did so back in 2013: ‘to protect, conserve and enhance the Union’s natural capital’.

The 25YEP objectives read like a catalogue of individual environmental issues – air, water, waste, biodiversity, environmental risks, climate change etc. By contrast, the 7EAP employs a cross-cutting approach, with connections to the enabling governance responses: better implementation, a stronger knowledge base, greater policy integration and coherence etc.

Some of these issues do feature in the 25YEP – such as policy integration. But in the UK plan its scope is limited to climate change, not ‘environmental concerns’ broadly. And the overriding aim is only to ‘take into account’ not to ‘ensure policy coherence when creating new policy’.

Finally, the EU’s programme is principally aimed at delivering upon policy goals in a better way. The UK plan is mainly focused on identifying old and new policy objectives. In the context of Brexit, this focus on defining aims is understandable – the government is keen to show it will not roll back environmental commitments (although its water quality targets appear to do so!).

The governance of the 25 Year Plan

Yet Brexit also raises a raft of environmental governance issues. The 25 YEP fails to address many of them. For example, there is the vexed question of devolution. On this the Plan baldly states that the UK government will ‘continue to work with the devolved administrations on our shared goal of protecting our natural heritage’ and confirming a consultation on a new independent governance body.

By contrast, the adoption of the 7EAP marked the end of a long process which started with the assessments of the 6th Environmental Action Programme (2002-2012). A proposal, built around addressing the 6EAP shortcomings, was influenced by stakeholder consultation before the final text was agreed by all Member States and the in November 2013. The 7EAP will then be independently reviewed by the European Environment Agency through its forthcoming 2020 State of the Environment Report, the Commission will also report to the European Parliament on its outcomes.

The clear governance framework underpinning the 7EAP throws in sharp relief the UK’s post-Brexit governance gaps. Only with the adoption of the EU Withdrawal Bill, a new independent body (addressing issues both of reporting and compliance) and a new way for the devolved administrations to work together – is the 25 year plan likely to be implemented in full.

Holding the government to account

Such a long-term plan is rare in UK environment policy. While it is far from perfect, it is an opportunity to hold the government to account for its ‘pledge to hand over our planet to the next generation in a better condition than when we inherited it’.

Environmental stakeholders can do three things to ensure this ambitious aim is delivered. First of all be clear about who is doing what, when and how. Much more work is needed to identify precisely where each 25YEP target comes from. Where the government is opting for different indicators from the EU – such as ‘resource productivity’ or ‘natural state’ of waters – it is vital to know whether adopting new indicators actually increases or reduces the overall level of ambition.

Second, focus on the government’s own intermediary deadlines. The ones included in the plan (a new set of metrics by the end of 2018, a new National Ecosystem Assessment starting in 2022) need to be met. Finally, the missing governance pieces – an independent enforcement body, that coordinates with the devolved nations and a clear framework for cooperation with the EU – need to be put in place.

There are plenty of important things to discuss. The Environmental Audit Committee’s new inquiry into the functioning of the plan has plenty of weighty matters to sink its teeth into.

About the authors

Dr Viviane Gravey is a Lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast. Andy Jordan is a Professor of Environmental Sciences at the University of East Anglia. Charlotte Burns is a Professorial Fellow at the University of Sheffield. They are co-chairs of Brexit & Environment.