Green Gove woos environment sector: But what about devolution?

Despite a House of Lords report published last week warning that the impact of Brexit on the UK’s devolution settlements is “one of the most technically complex and politically contentious elements of the Brexit debate”, the issue of devolution has received little attention in the public Brexit debate.

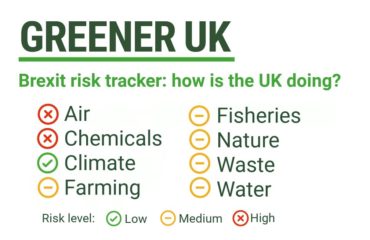

Even less attention has been paid to how the post-Brexit devolution settlement will impact the environment, with the environment secretary Michael Gove in his first keynote speech on creating a ‘Green Brexit’ completely ignoring the issue of how this devolved issue will be governed once we leave the EU.

The House of Lords report highlights some critical issues that need resolving if we are to avoid political conflict and effectively deliver environmental policy goals.

What about devolution?

As environment is a devolved issue, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have created their own environmental policies, with shared minimum standards yet scope to pursue differing ambitions. But when the UK leaves the EU and the responsibility for (devolved) policy areas such as agriculture, fisheries and environment automatically fall to the devolved jurisdictions there is an increased risk that policies will start to diverge significantly – leading to potential political conflict and barriers to trade.

The cracks in the surface have already started to emerge, with the First Ministers of Scotland and Wales, Nicola Sturgeon and Carwyn Jones, criticising the Withdrawal Bill published last week for being a ‘naked power grab’ by Westminster, arguing that it fails to return EU powers to the devolved administrations.

The tensions are perhaps understandable, as the agricultural and fisheries sectors are considerably more important to the devolved nations’ economies. Farmers in the devolved nations rely more heavily on subsidies and funding through the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy than farmers in England, for example, and are also more dependent on EU migration to meet labour market needs in these sectors.

The House of Lords report therefore urges the government to engage more closely and cooperatively with the devolved governments, and to respect their national, regional and local diversity. They warn that the common standards that need to be developed post-Brexit to protect the environment, maintain the integrity of the UK single market and enable trade must not be imposed in a top-down manner.

To this effect, they encourage the government to ‘raise its game’ in making the Joint Ministerial Committee (European Negotiations) (JMC) more effective. This should be done by having more regular meetings and a structured work programme, by authorising the JMC to agree common positions on matters affecting devolved competences, and they recommend that its meetings should be synchronised with the cycle of Brexit negotiations to allow the devolved governments influence on proceedings and for the government to report back. This would indeed be an improvement in the governance architecture. Only this morning, First Minister of Wales, Carwyn Jones, complained on the BBC Radio 4 programme Today that there had been little discussion between Westminster and the devolved administrations, arguing Wales wanted policy by ‘consent’ not ‘imposition’.

Another issue, pointed out by the House of Lords Constitution Committee, is the lack of a ‘guiding strategy or framework of principles to ensure that devolution develops in a coherent and consistent manner’. With regards to the environment this is particularly important. So far, the different environmental policies across the UK have retained coherence through EU principles of law – such as the precautionary principle and the polluter pays principle – which underpin their implementation and enforcement. The status of these EU principles in UK law post-Brexit is uncertain, however, increasing the potential for policy divergence and clashes between the devolved nations and Westminster. As a result, leading green groups have called for the principles to be transferred fully through the EU Withdrawal Bill.

Mind the governance gap

Finally, although it receives almost no attention in the House of Lords report, the implications of the ‘Governance Gap’ for the devolved nations should receive more attention. Concerns over the UK’s administrative capacity to develop, implement and enforce new policies – typically done at the EU level – are particularly acute for the devolved nations. With responsibility for environmental policy, the devolved administrations have even fewer staff and resources than Westminster to implement and enforce policies, leading to fears of ‘zombie legislation’ (policies alive on the statute book but effectively dead for lack of capacity to ensure efficacy).

As such, it was disappointing that Michael Gove was silent on the issue in his speech. How environmental governance should be structured post-Brexit is a complex and contentious issue that should be highlighted – not hidden – in the public debate.

About the author

This blog post is written by Dr Fay Farstad. She is a postdoctoral research associate on the project ‘Brexit and the Repoliticisation of UK Environmental Governance’ funded by UK in a Changing Europe.